In General

Africa was not always as we now know it, but once part of a great southern continent called Gondwana; comprising Australia, India, Antarctica, South America and Madagasacar.

A large inland basin developed in Gondwana wherein sands and muds were deposited from about 300 million to 183 million years ago. These sediments comprise the Karoo Sequence which now covers nearly half the surface area of South Africa.

This stable period ended 183 million years ago with the flood of Stormberg basalt lavas onto the land surface. The Lesotho Highlands are remnants of lava fields formerly extending as far as Botswana and Zambia.

A widespread system of vents and fissures acted as channels for the lavas to journey to the surface. The molten lava that solidified in these systems now form near-vertical dykes and sub-horizontal sheets of dolerite. Dolerite differs in texture from basalt, a result of cooling more slowly.

Later, at about 120 million years ago, build up of stresses in the earth’s crust caused cracks and rifts of continental extent to develop and Gondwana began breaking up. Over the next 30 million years the Atlantic Ocean opened and South America moved westward while Antarctica, India, Australia and Madagascar moved away from the east coast of Africa.

All this activity caused widespread faulting and fracturing of the Karoo rocks in much of KZN followed by later earth movements as the continent continually adjusted to the stresses caused by the planet’s internal ‘engine’. A long period of erosion was initiated. Rivers ate back from the new coastline, continually reducing the topography, an action continuing to the present day.

At The Cavern

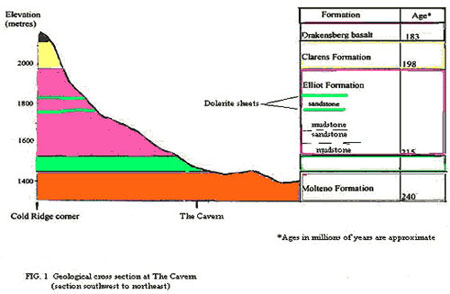

Only the top few hundred metres of the Karoo Sequence are present. Termed the Stormberg Group, geologists have sub-divided the Group into three Formations on the basis of depositional and environmental histories. These formations, the Molteno, Elliot and Clarens formations, are capped by the Stormberg basalt lavas.

At Sandstone Lodge one is standing on Molteno Formation rocks, the oldest at The Cavern and dominated by sandstone. Looking eastward, the river has cut into the hillside exposing thin alternating units of fine sandstone and mudstone.

Looking up toward the mountains from Sandstone Lodge or The Cavern Hotel, a layer-cake system of rock units is seen, defined by hard sandstone ledges separated by softer weathered mudstones as shown in the cross-section of Fig.1 (at left).

Changing environments

The mudrock-rich Elliot Formation is sandwiched between the sandstone-rich Molteno and Clarens Formations. Thicker sandstone units within the Elliot Formation, more resistant to erosion, form ledges up the mountain slope culminating in the impressive creamy to greyish cliffs of the Clarens formation. The basalts are small blackish remnants atop some of the highest points.

From this sequence geologists have deduced the changing nature of the river systems depositing the sediments, and climates under which they operated,

(Table 1).

| Formation | Main Rock Types | Environment of deposition | Key fossils |

| Drakensberg Group | Basaltic lavas | Continental scale rifting | No fossils |

| Clarens | Fine-grained sandstone & siltstone | Dune covered desert with seasonal rivers (wadis) | Dinosaur and fish fossils |

| Elliot | Red-maroon to green mudstone + minor sandstones | River systems in semi-arid to arid flood plain | Dinosaurs, (Massospondylus, Euskelosaurus) Earliest tortoise |

| Molteno | Alternating mudstone, sandstone, shale + coal seams | Braided river systems, lush vegetation | Abundant plants and insects; early dinosaurs |

River systems went from high energy rivers capable of carrying large sand loads in the Molteno Formation, to low energy meandering rivers in flat flood plains that regularly overflowed their banks depositing fine muds in the Elliot Formation, to flash floods and sheet flow in seasonal rivers of the arid Clarens Formation.

Periodic earth movements rejuvenated rivers during Molteno and Elliot times, with a sharp increase in coarseness and thickness of sands being deposited.

Climates over this period steadily dried out; from cool to temperate and humid for the Molteno Formation, as evidenced by abundant plant fossils, to semi-arid in the Elliot Formation and desert conditions in the Clarens Formation.

In Molteno times an estimated 2000 species of plants existed, with reed-like horsetails, conifers and gingko species prominent. This lush environment played host to an estimated 20,000 species of insects dominated by beetles and cockroaches.

The Elliot Formation saw the evolution of small to medium size dinosaurs; the environment could not possibly support the giants found in northern hemisphere lands.

In Clarens times the environment was even harsher and only small dinosaurs could survive.

Landscape

The Gondwana breakup and continental adjustment affected much of KZN, with severity of faulting and disruption decreasing away from the present coastline. At the Cavern these effects reduced to small faults and fractures where vertical displacement of rock units is usually measured in metres or tens of metres.

These features as well as the hard and soft sandstone and mudstone sequence, acted as controls on the developing landscape. Small faults and fracture zones control development of stream courses and fractures define cliff faces. Thicker hard sandstone layers produce resistant ledges and cliffs.

The Cavern: Walking trails and Geosites

Common Features

- Mud slide scars

Water saturation of soils and loose rocks increases their weight considerably. On steep slopes the weight becomes too great to be maintained in position and the mass slides, leaving a bare scar on the hillside. A mudslide can be seen close-up on the Grotto walk as you start the final descent. The path skirts the scar just before descending. - Potholes

At The Natural Pool, where the stream enters, potholes have developed. The force exerted at the base of the waterfall by the water is considerable. That, and the sand grains it carries, act to scour out a hollow. Grains swirl around deepening and widening the hollow. Larger grains and pebbles are then trapped, continuing the process. - Cross- bedding in sandstones

Cross-bedding, as the name implies, comprises sets of inclined bedding, developed in river systems under varied flow conditions. Commonly they are bounded top and bottom by near-horizontal surfaces, (normal bedding planes), to form tabular units. Cross-bedding indicates ancient hydrodynamic conditions and prevailing current directions. In turn, the source area for the transported sands and muds is indicated.- The Silent Lady offers good examples. Walk upstream 30 m look left and several sets of cross-bedding can be seen in the sandstones.

- Fracture zones

These are not always obvious but control many of the streams and spruits in the area, as well as indicating future stream courses. They provide weaknesses exploited by stream erosion. Mudstone fractures easily and weathers out from under sandstone layers until local collapse of the sandstone occurs. Trees then colonise the depression and thrive, being protected from fire in their tender stages. As time goes by, further collapse occurs along the zone and a stream is born.A good example of the process is seen on the Grotto walk. Emerging from the pine trees one crosses a donga straddled by a tree. This is recent as local guides recall a time when there was no donga. Looking right, a clump of trees in the donga mark one of the initial collapses. - Dolerites

Three dolerite sheets are present, the thickest being in the area of the The Cavern resort and extending to the waterfall, the weir, and around to Sungubala Camp. The location is on, or close to the contact between Molteno and Elliot Formations where inherent weakness between hard sandstone and soft mudstones has been exploited.Two much thinner sheets, bracket the upper thick sandstone in the Elliot Formation at its contacts with mudstone.No dykes were found on the property but at the first cutting at the base of Oliviershoek pass, a near-vertical dyke has intruded sandstone.

As added interest to walkers and hikers geosites along several trails across the different formations are described.

Silent Lady Walk

Outward via Bushbuck Ridge, return by Sandstone Lodge. From the hotel across the river to the top of the ridge you remain in the dolerite sheet. Note the yellow angular pieces scattered along the path. The yellow colour is due to iron oxides produced by alteration of iron-rich minerals in the fresh rock. Break open a piece to see the fresh blue-black crystalline rock inside.

Bushbuck Ridge itself marks the top surface of the dolerite sheet. This same sheet continues around to form the ledge backing Sungubala Camp.

Close to the Silent Lady, Molteno Formation sandstones outcrop. These lie below the dolerite sheet traversed earlier. Approximately 30 metres upstream of the Silent Lady, is the location of multiple sets of cross-bedding in the sandstone cliff.

On the left side a thin finely cross-bedded unit is more susceptible to the elements and has weathered out more rapidly than the thick cross-bedded units above and below. An overhang of the thicker sandstone has developed which will, in time, collapse into the river when the weight of the slab exceeds the strength of the rock.

On the return journey the road down to Sandstone Lodge reaches a bend with gum pole railing. A road-cut begins here, exposing crumbly beige mudstone which gives way downhill to a layer of dolerite rubble and soil overlying sandstone with a thin mudstone layer. The loose dolerite has migrated downslope from the sheet higher up by action of rain and gravity.

The Natural Pool walk

Follow the path to the Silent Lady onto the top of the dolerite sheet. Continue until the path splits. A sign-posted path descends down to the river and The Natural Pool.

The Natural Pool

Why is it there? Look at the river course – it changes direction abruptly. Two fracture systems intersect creating a weakness exploited by the river.

Potholes – where the stream enters the pool two potholes have developed.

Smaller potholes occur in the sandstone outcrop on the left of the pool by the shelter.

Dessication cracks – a polygonal pattern of lines by the small potholes is due to cracking as sands dried out during periods of low water flow.

During floods water plunges into the pool with its load of sand and pebbles, flushing them through to the far side where they deposit as sand and pebble bars that can be seen immediately downstream of The Pool.

Waterfall Walk

This short walk branches off right from the Fern Forest path before it crosses the river. The path down to the waterfall is signposted a short distance further on.

The pool below the waterfall flows out through a gap defined by smooth joint and fracture planes. The same planes can be seen on the left side of the waterfall and are part of a fracture zone controlling development of the river course.

The cliff face on the north bank shows many curved joints; produced when the molten dolerite solidifies and shrinks in the process. Close to the surface the joints open up and are exploited by tree roots.

Look at the loose rocks in the river bed. Some are rounded having been tumbled and rounded by the river from much further upstream. Others are angular and derive from local dolerite outcrop.

The Grotto Walk

In the pines the path is still in the dolerite sheet. It then crosses the fracture controlled donga and continues to a hairpin bend, initiating descent to The Grotto. The path skirts a mudslide scar at this bend.

The Grotto

Ripple marks, similar to those seen today on beaches and in river beds, are present on the sandstone surface as you step down into the Grotto. They show up well in early morning sunlight.

Look right at ground level; thin alternating brown and grey mudstones have weathered back to create an overhang of sandstone. These mudstones are not seen on the other side of the grotto. As beds are near-horizontal they should be there. What happened?

Movement on a fracture zone controlling The Grotto stream has dropped the mudstones down on the southeast side. Now go downstream a few metres where the spruit leaves the grotto. Look under the slab of sandstone you will be standing on and see how cracked and broken the mudstone is underneath.

The Grotto to Fan Falls walk

The path from the south side of The Grotto branches toward the top of the first ledge. Take the left fork. The undulating path is on fine sandstones. Blocks of coarse gritty sandstone from higher up have fallen down a small spruit. Compare the grain size to sandstones you have seen before. This same sandstone occurs on Echo Cave walk as well.

Continue on towards Fan Falls. The path crosses a small depression. A single pothole has formed next to the path, a most unlikely place for one.

Why is it here? The spruit course to the left is straight, exploiting a fracture that roughly parallels the cliff face, itself a fracture line. To the right the spruit has a sinuous course indicating the fracture has been terminated, possibly by one of differing orientation. This weakness could only have been actively exploited during rainy seasons. High energy floodwaters would account for the size of the pothole and large pebbles trapped within it.

Close to Fan falls red and beige mudstones with thin sandstone beds occur, extending upslope to the next thick sandstone layer. A cliff edge to the thick first ledge sandstone provides the drop for the Fan Falls.

Echo Cave Walk

The dolerite sheet is present throughout the Fern Forest part of the trail. Yellow weathered dolerite is shown in path cuttings. On emergence from the forest two things are noticeable; firstly the sharp straight boundary to the forest, and secondly there is no more dolerite only sandstone. A small fault has displaced the dolerite from surface in the forest to depth west of it. A stream has exploited the weakness provided by the fault, enhancing the boundary.

Climbing the hillside toward Rustler’s Gap, beige to grey mudstone is occasionally present on the path. As it weathers easily it is not often seen. Beyond the first stile, coarse sandstone indicates the start of the upper part of the Elliot Formation. Looking southwest across the valley there is a spectacular view of the Clarens Formation cliffs. Look also for a series of tree clumps forming a straight line up the slope on the far side of the valley. These indicate a fracture zone, the tree clumps indicating local collapse. The return path takes you past one of these clumps.

At the second stile there is a clump of trees on the right against a steep slope. They have been protected by a minor collapse structure developed over the same fault defining the forest edge. It may have been induced by the rock-fall of large sandstone blocks scattered around.

A recent mud slide scar can be seen beyond the bend in the path leading up to Rustlers Gap.

The last blue marker the on the path is close to the contact between Elliot and Clarens Formations.

The mudstone has a number of features indicative of flash flood type deposits. Clay pebbles are scattered throughout, recognized by their lighter colour where broken. Their long axes are not aligned parallel to the bedding, as would be the case in a perennial river.

A thin slab of fine cream sandstone is a remnant of a larger band broken up by the flow.

The top of the red mudstone fingers into a blue mudstone upwards, which in turn is overlain by thick creamy Clarens Formation sandstone of the cliff face. This sequence persists around to Cannibal Cave

Further to the right, a long block of the red mudstone has been squeezed or ‘popped’ out from the base of the cliff. Note the concave fracture surfaces on the cliff mudstone where failure occurred.

Small faults and fractures cut the sandstone cliffs into blocks, each of which behaves slightly differently under stress. Events like earth tremors can affect these blocks differently with stress release through fracturing of the long suffering mudstone. As the mudstone layer retreats into the base of the cliff, the sandstone above becomes stressed to the point where partial collapse occurs, creating the shelters once used by the San people as living space.

At the far end of Echo Cave itself distinct cracks are opening up.

On the round return trip, just past the first fence, is another slump scar. Material slid into the stream exposing yellow and red mudstones. Further on just before the path splits, note a clump of trees in a dip; part of the fracture zone you saw from Rustlers Gap.

Oliviershoek Pass: dolerite dyke

No dykes have been found at The Cavern but at the base of Oliviershoek Pass a dyke has intruded sandstone. It is well jointed in the centre and weathered on either side. The edges though are still fresh and hard having chilled on contact with much cooler sandstone. A thin dark brown sinuous band, a fracture, slices up through the dyke; due to later movement, either from the Gondwanaland breakup or later.